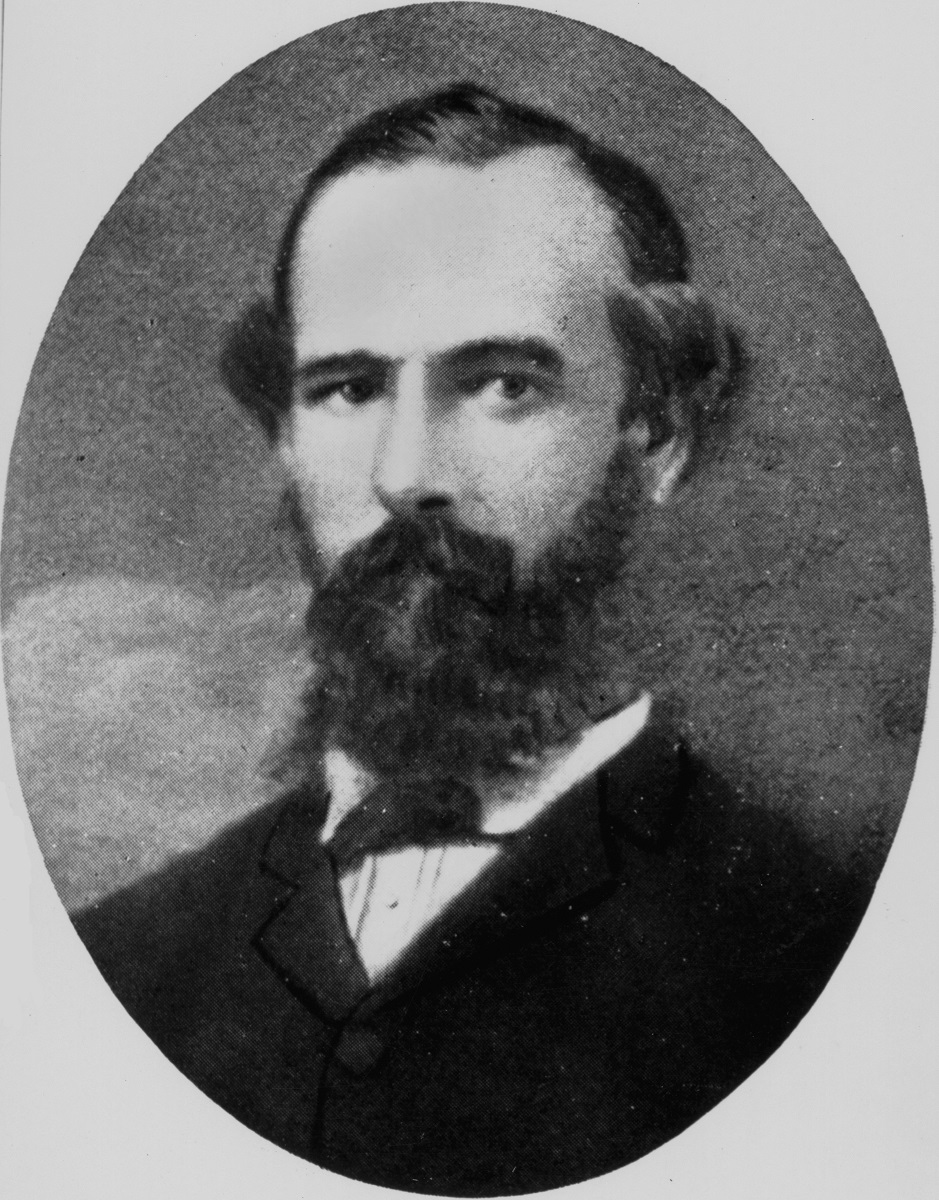

Thomas Cuthbert Coolon was born in Richmond, New South Wales, on the tenth of April 1859. His mother, Sarah Douglass, died when he was seven years old. His father remarried and moved out west of the Darling River where Tom was abducted by a group of Aborigines.

For the next decade Tom was raised by wild blacks, learning and honing bush skills that would become legendary. He also learned harsh laws of retribution and payback that would lead, later in life, to a shocking tragedy.

As squatters and their stock pushed further out into the scrub Tom found himself once more part of white society. With his lean frame and general toughness he quickly fell into station work. Some cattle stealing on the side saw a policeman ride out with an arrest warrant in Tom’s name.

Tom, however, had the “trap” in his sights long before he arrived, and shot the horse out from under him.

This, it seemed to Tom, was a good time to take a change of scenery up in Queensland where he worked as a ringer, dog-baiter, and roo-shooter. In his spare time he developed an interest in prospecting.

Tom was a striking looking man; tall with blue eyes and a blazing red beard. In 1890 he married Catherine Mongovan. The couple had two daughters and a son, living in the Clermont district, Queensland.

The turn of the century saw Tom droving with Ted Drewer up to the Territory, taking a mob of brood mares to one of the vast Fisher and Lyons properties. When the mares had been delivered he headed for Darwin, intending to take a ship home to Queensland. The wet season had struck early, rivers were flooded and impassable all the way down the Top End and across the Gulf country. Riding home would have been impossible.

News hit Darwin of a droving camp near Newcastle Waters facing starvation and fever, cut off from the world. A desperate call went out for a volunteer to ride five hundred miles south with supplies for the stricken men.

Tom Coolon stepped forward, and with three riding horses and two packs he set out on a mission few men would have attempted.

Swimming the horses across flooded rivers he managed to cover an astonishing fifty miles each day. Sadly that perilous rescue mission came too late, for the last of the drovers died on the day Tom arrived.

Tom was now a legend in the Territory, but back in Queensland things went bad. First, the Coolons’ twelve-year-old daughter Mary died. Then Tom took up a partnership on a station called Prairie Run, near Clermont, but the business arrangement degenerated into a bitter feud that included the odd gunfight.

Tom and Catherine took up the adjoining property, Spoonbill Farm, but Tom’s former partners, the Kirkups, were out to get him, framing him for the possession of stolen livestock, a “crime” that saw him imprisoned for two years at hard labour.

After his release Tom Coolon was a changed man.

It was race day in Clermont when Tom came up against the law again. He was drinking at the pub when a stranger tried to pick a fight. The two men were shaping up when a huge policeman called Ormes banged their heads together and threw them against a wall.

Legend has it that Tom Coolon slowly stood up, then fixed his eyes on Constable Ormes. “I won’t forget this. It will be evened up.”

When, a few months later, the policeman’s corpse was found at a place called Camp Oven Hole on the Charters Towers Road, Tom was naturally a suspect.

From a recollection in the Townsville Bulletin:

It was in that country later that Constable Ormes was shot at the 33 Mile, better known as Camp Oven Waterhole, on the Clermont-Charters Towers Road. The head of Ormes’s horse was still hanging on a limb of a tree when I was along that road in 1938. It seems whoever did it, shot the horse behind the shoulder and then killed poor Ormes with either a stick or a rifle barrel.

Australian folklore has had Coolon pinned as the murderer ever since, but an eyewitness report by an old man called “T.C.W.” fifty years later clears his name.

Coolon (was) an outstanding bushman and a deadly rifle shot; he could hit anything as far as he could see. I knew Coolon very well, and he could be a good friend. I also knew Mrs Coolon, a fine Irishwoman, their eldest daughter Violet, and son Hector, the latter only a baby then. Regarding Constable Ormes’s death on the Charters Towers-Clermont road, there was no foul play; he was not murdered nor was his horse shot.

I was coming into Clermont from the Suttor River about 1903, when, at the 60 Mile on the Charters Towers road, I found a dead man, perished from thirst, about three miles on the Clermont side of Lanark Station on Mistake Creek, then deserted. I pushed on to the Black Ridge Hotel. It was a gold mining place that was in full swing at the time, twelve miles from Clermont.

I reported finding the dead man to the police. Constable Ormes was sent out to bury the dead man. It was about three days to Christmas and very hot weather. So he rode out and stayed at the hotel that night and left next morning for the 60 Mile to bury the man. He said he could do it and be back that night, a round trip of 96 miles, no water anywhere, and only one horse to do the journey. He reached and buried the man and was no doubt trying to make the journey back in the night, was very thirsty and his horse galloped off the road and ran into a fallen tree. This killed the horse, and the policeman was found dead some distance away from the horse; the limbs of the tree were responsible for his death also.

Either way, Tom Coolon went about his business, kangaroo shooting in the Belyando River country, prospecting and working as a stockman. As one of his old comrades wrote:

(Tom) was also a marvellous bushman, and as a buckjump rider he was above average, although not in the Lance Skuthorpe class. Coolon was never guilty of riding a poor or weak horse, and if a buckjumper ran loose he would ride him, but not in a yard. He was one of the cleverest scrub riders that ever steered a horse through the mulga.

Though he loved horses, Tom had a mortal fear of dogs, and would not suffer them anywhere near him. He would never refuse a bet, one night riding seven miles with no moon to locate a tomahawk he had left in the scrub, winning twenty pounds in the process. He also spent much more time away from his wife and children than near them. This last fact must have occurred to him, and he decided that it was time to settle.

One day, working around Yaccamunda Station, Tom came across a recently-pegged gold mine. The owner was nowhere to be seen. A few washes with the pan, however, told Tom that it was a rich claim, and he decided then and there that he wanted it.

The gold mine that Tom Coolon found on Yaccamunda Station was in a remote area, far from other diggings. With his knowledge of prospecting Tom suspected that it would be the start of something big. He cunningly learned everything he could about the man who had pegged the claim.

The words on a claim notice fixed to a stake meant nothing to the illiterate Tom. He instead used his tracking skills to learn of the claimant’s movements. Footprints led to a nearby campsite, a small waterhole, and finally, horse tracks heading north towards Charters Towers.

Tom must have grinned to himself when he realised that the claimant was heading in the wrong direction. Mineral rights in this area, he knew, were under the jurisdiction of the mining warden in Clermont, to the south. Without wasting any time Tom saddled up and galloped off to find the warden, registering the claim in his own name. He was in full, legal possession of the claim when the man who originally pegged it, Luke Reynolds, arrived.

Reynolds had ridden all the way to Charters Towers, only to be told that he needed to go to Clermont, and was calling in to check on his claim on the way through. Tom was ready and waiting, his trusty lever-action Winchester close at hand.

‘Who the bloody hell are you?’ Reynolds asked.

‘I’m the legal owner of this claim,’ Tom replied. ‘So if you value your life you’ll turn around and keep riding.’

Reynolds was too smart to take Coolon head on, instead talking him into a partnership. This arrangement lasted only a few weeks before it fell apart. Reynolds decided that discretion was the better part of valour and pegged a new claim just along the ridge.

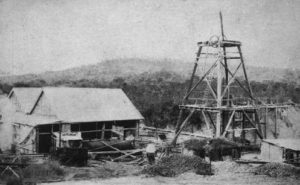

By this time Tom had built a sturdy hut and brought Catherine out to live with him. His mine had a thick seam of gold-bearing quartz, and hundreds of diggers flocked to the area, now named Mount Coolon. Within months the first stamper mill was on site, crushing piles of rich ore for the miners.

Finally, in his fifties, things seemed to have come together for Tom Coolon. He lived at home with Catherine. They had a garden and a flock of goats. The mine was making good money without too much hard work.

Yet, with no employees, Tom was obliged to travel away at times for supplies. Greedy eyes were watching when he rode off to Clermont with Catherine in late October, 1918. Under the law at the time a claim became void if it was left unattended by the owners.

Mount Coolon in 1932. John Oxley Library

A mining entrepreneur called Bernard Thompson waited until Coolon had been away for a few days then went to the local mining warden, filing for forfeiture of the mine because of Tom’s absence. The warden backed him up, and Thompson now had title to the mine, obtained in a similar tricky way to how Tom had stolen the mine in the first place.

Thompson took on three partners to help work the claim: Harold Smith, Robert Wells and William Brown. When Tom returned from Clermont he found four armed strangers in legal possession of his mine. He flew into a terrible rage, demanding that the men leave immediately. They stood their ground. Thompson had decided to take Tom on in full knowledge of his reputation. He too was a hard man, and not easily cowed. Tom filed an appeal against the warden’s decision but the District Court confirmed the forfeiture.

Tom was forced to watch from his hut as Thompson and Company brought gold ore up from the depths of a mine he had dug with his own hands.

On the morning of Wednesday November 13, 1918, Tom walked to the camp of a man called Charles Woodland, a JP, and asked him to take down his last will and testament. Once this was done, signed and witnessed, Tom walked back to his hut, fetching his Winchester and horse.

Riding up to his old claim he saw Bernard Thompson working up top. ‘You’ve got five minutes to get off my claim,’ Tom said.

Thompson shook his head. ‘I’m not going.’

Tom raised the butt of his rifle to his shoulder and fired into the ground between them. Thompson went for the revolver on his belt. He fired but missed, and Tom’s second shot took him under the arm, the third ploughed into his chest, killing him.

People had heard the shots, and news of Tom Coolon taking vengeance with a rifle spread like a grass fire. Men dived down mineshafts and hid. One of Tom’s targets, Robert Wells, reckoned he owed his survival to sheer laziness, for he was having a smoke down the mine and couldn’t be bothered going up when he heard someone yelling for him at the top.

The Native Bear Mine: John Oxley Library

Tom stopped at the Native Bear mine where he found an employee of Thompson’s called William Bloom, who turned and ran. But to the old roo hunter a running man was easy prey. He brought him down with one shot.

Another man that Tom had intended to kill – Alexander Smith – fell to his knees and declared that he was Tom’s friend, and that they had no quarrel. They shook hands and Tom declared that his plan was to kill a few more men and then “do himself in.”

Tom rode fast, ahead of the rumours, to the stamp mill two miles away. There he found two more of Thompson’s associates: Harold Smith and William Brown. He shot them both dead.

Finally, having killed four men all up, Tom rode off into the bush, leaving Catherine at home in the hut. Police from all over the district, led by an Inspector Quinn, scrambled to collect bodies and come to terms with what had happened.

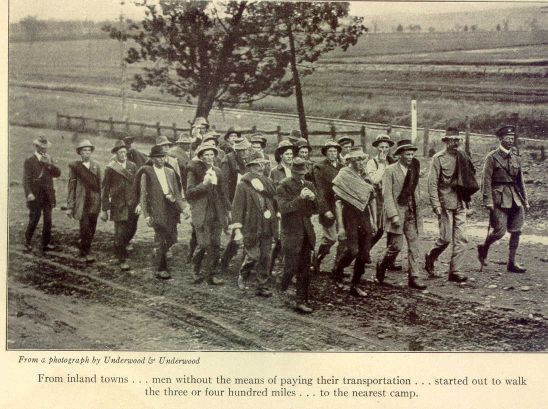

A manhunt of epic proportions followed, but Tom, with his bush skills, had no trouble evading the police. Every man who had ever had reason to argue with Tom Coolon now believed himself a possible target. There was a sudden exodus from Mt Coolon and also Clermont of men who believed themselves to be on his hit list. On horseback and motor vehicle they fled, vowing to stay away until the murderer was caught.

Three days after the murders, however, Tom slipped through the police cordon and rode home to the hut he shared with Catherine. He kissed her for the last time, then turned the gun on himself. They found him there, in a pool of blood, with his wife of almost thirty years crying over him.

Browse our books here.