Charlie Gaunt was in his late thirties, veteran of the Northern Territory cattle trails, and a hard-fought Boer War, when he began several decades of international wandering. His willingness to work as a seaman took him wherever he wanted to go.

Since Whistler’s Bones is essentially a novel about Charlie’s Australian experiences, there was no room for these stories, but they’re fascinating nonetheless, and it’s great to be able to post them here.

The Slave Ship by Charlie Gaunt appeared in the Northern Territory Standard newspaper on the 6. 10, and 13th of November, 1931.

Broke, in the Sailors Home Calcutta, sitting on a bench amongst a lot of old seasoned shellbacks; men who had sailed seven seas; schooner men, whale sealers from the Pribilof Islands, men who had been in the blackbirding trade in ‘the southern seas,’ young lads who had only done their first or second trip at sea.

Old and rugged were some, with hands knotted and gnarled, impregnated with Stockholm tar that would not wash off, and the grip of an Orang Outang. Faces seamed and scarred with the gales of the Arctic and howling typhoons of the China Seas. But, age counts nothing, the shipowner wants your work, not your body, and a “Bucko Mate” is there to get it out of you and he gets it, or you’ll wish yourself in hell for signing on for job you cannot fulfil. Officers and crew have no time for an inexperienced man or a slacker.

What tales those old seamen could tell, a couple of nobblers of rum and a plug of tobacco would draw them out of their shell. And I with my limited experience of the sea, only on luggers, pearling, felt very small amongst that seasoned brigade. But I was desperate. I’d have shipped aboard a Nova Scotia blood ship. Too long had I stood the famine and I was getting fed up and longed for the feast. All the crowd at the Home was dead broke. You could not squeeze a rupee out of the lot and every man eager to get ship and the coveted advance note (a month’s pay in advance before going aboard after signing articles) and having a night’s outing amongst the girls and the rum, before embarking on perhaps a floating hell.

We all sat on those benches in that big room in a listless manner, scheming how we could raise the wind for a bit of tobacco or a bottle of rum. Presently, while we were moralising over our past sins, the Runner of the Home came in and in a loud voice said, “Who wants a ship for the West Indies?” We all jumped to our feet. He continued, “Ship Mersey loading twelve hundred and fifty coolies at Kidderpore Barracoons, sailing day after tomorrow’s tide. AB’s (able seaman) is fifty four rupees per month, ordinary seamen thirty rupees. The run is one hundred and twenty five days, more or less, destination Port of Spain, Island of Trinidad. Now boys, who’s going to ship? I want a double crew, thirty two men (Indian coolie ships were compelled to carry double crews).

Every man in the room in one voice said, “Aye.” Twenty eight of us, and headed by the Runner we marched to the Shipping Office. When we entered the office the Captain was there, and the Shipping Clerk sat with the articles before him on the desk. We all lined up and Captain Douglas, of the Mersey sized us up. He looked us up from the feet to the chin. Muscle and thew he wanted, brains didn’t count. Signing the A.B.s first who were handed the articles and conditions of food, to read. If satisfactory they signed their name and received the Advance Note with the remark from the Captain, “Be aboard before midnight tomorrow.”

I was fifth in the line and when I read the articles, “Three years or any Port in the United Kingdom.” I handed the paper back to the clerk with the remark, “Cut me out, I’ll not sign those articles.”

“Why?” asked the Captain. “They are in order.”

“In order,” I said, “but when you land those Coolies in Port of Spain, where do you go from there?”

The Captain said, “We load sugar at Barbados for New York, thence to Pensacola and load hard pine for England, and then you get your discharge.”

“I’ll sign for Port of Spain,” I said, “and no farther. Give me my discharge in Trinidad and I’ll sign.”

The skipper sized me up and seeing I was a likely looking A.B. said, “All right. I’ll sign you off in Port of Spain.” (It took, as I afterwards found out, nearly three years for the “Mersey” to reach Great Britain). I then signed the Articles and after the Runner got the rest of the men and they all signed on we got our Advance Notes went out, cashed them and then hit the high places. The following evening I, with part of the crew, went down to Kidderpore docks, found the Mersey and went aboard.

The Mersey was a full rigged steel ship, about three thousand nine hundred tons, hailing from Liverpool, England, and with her sister ships the Elbe, Lena, and Rhone she was engaged in the coolie trade of the West Indies. Stragglers came to the Mersey all through the night, some drunk and muddled and threw themselves into the bunks of the forecastle to sleep off the effects of the liquor. About midday the tide being in full flood and the crew all on board the tug boat Hugli took hold of us pulled us out into stream and like a toy terrier pulling a huge mastiff, towed us out of the river to the sea.

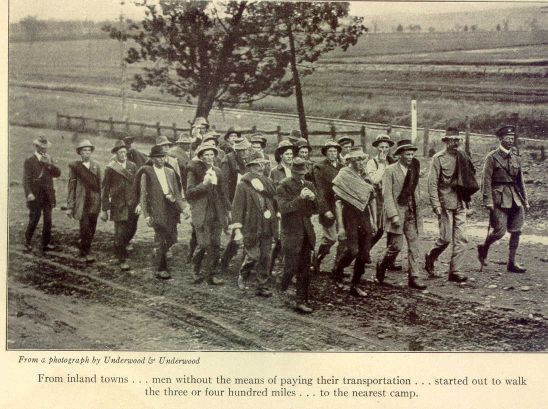

Before continuing this article a word regarding the West India coolie trade. Babus (recruiting agents get into the farming districts in Province of Bengal. With a promise of big wages and a glowing account of the land he is going to, only, says the Babu, distant about one day from Calcutta, he gathers the unsuspecting coolies in mobs, takes them men, women and children, to Kidderpore Barracoons three miles below Calcutta (Barracoon being a big walled in compound) and once the Babu gets them in, the massive gates are shut and coolies carefully handled and are kept until the number required is got together, and then put aboard. The coolie for the plantation of the West Indies is indentured for three years at a wage of eighteen pounds per year and food and housing. When the coolies find they have been deceived regarding one day’s sail from Calcutta and for days see only the open sea they try to jump over the side and drown, which many succeed in doing, as a Bengali loses caste when he crosses the sea.

Now the white doctor in charge of the coolies looking after health and welfare gets a guinea a head on safe delivery in Port of Spain, the Captain ten shillings, the mate seven and six pence, second mate five shillings and third mate half a crown, and the crew nothing, only work.

On the way down the river the mate mustered all the crew at the break of the poop to divide us into watches, he taking one watch, the second mate the other. Thirty-two of us lined up, the mate leaning over the rail closely inspecting us as a pig judge would inspect a pen of prize pigs. Amongst the crowd was big burly Swede, pipe stuck in his mouth. The Mate noticing it left the poop rail, walked down the ladder, strode up to the Swede and dealt him a smashing blow in the face, laying him flat on the deck, remarking: “Smoking is not allowed aft on this hooker.”

I said to myself, “A twenty-four carat Bucko Mate alright” and later on I found it out. The mate and the second mate then picked their watches, the mate taking port watch, second taking starboard watch. Sixteen men on each watch, and it fell to me to be one of the Mate’s watch. After the watches were picked the Mate climbed the ladder and leaned over the poop rail and as we started to walk away he called us all back. “Now men,” he said, “any man who has shipped aboard this ship as an able seaman under false pretences and he cannot hold his end up, I’ll make him wish he had never been born. You’ll find me a hard mate, but we’ve got twelve hundred and fifty lives on this ship and we want seamen, not farmers. Do your work and keep a civil tongue in your heads and when and addressing an officer, say, “Sir,” and you’ll find me a just man.

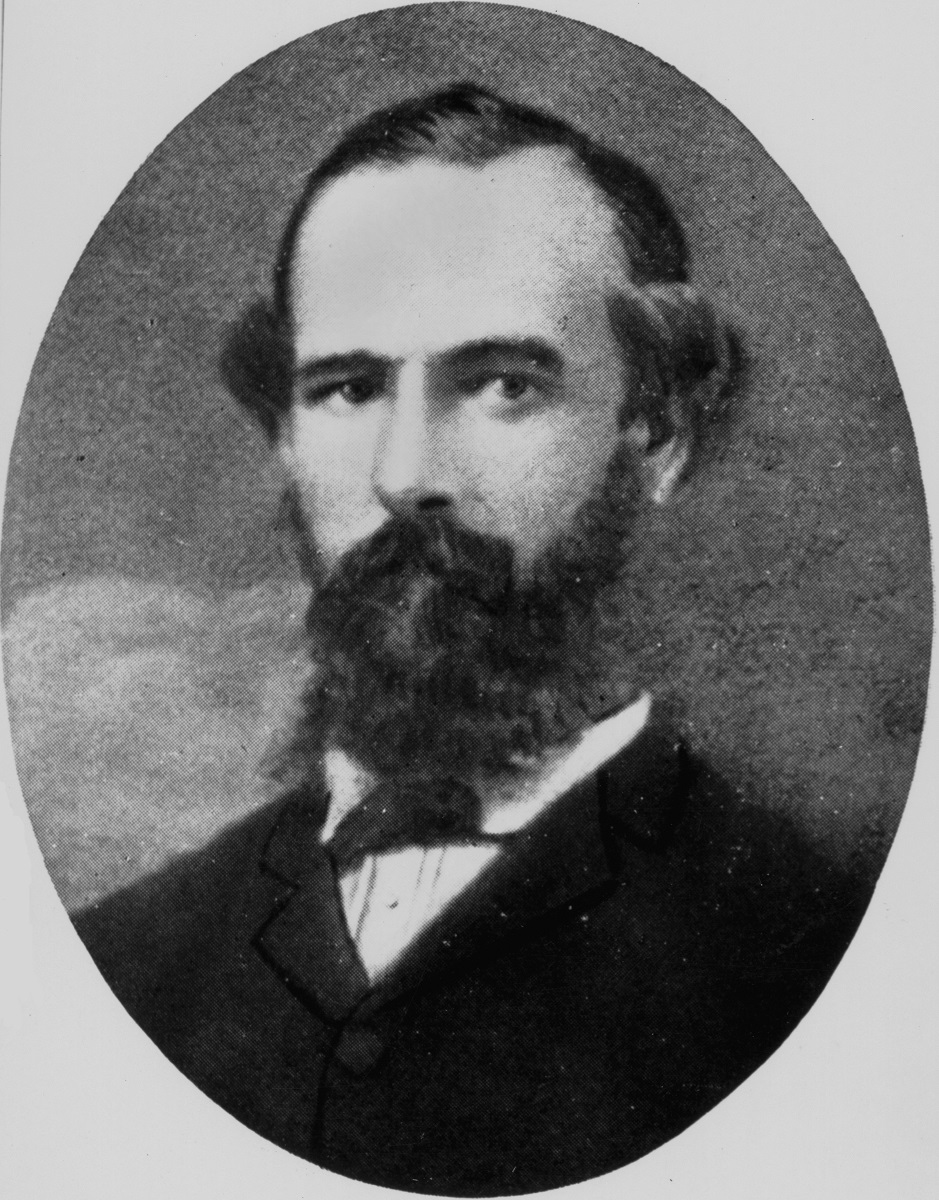

Captain Douglas knew his mate, a hard mate but one of the finest seamen who ever trod the deck of a ship. Armstrong was his name, a Bluenose (Nova Scotian) about thirty five years of age, tall and wiry, weighed about twelve stone, as agile and active as a cat, knew no fear and could hit like a sledge hammer. Truly a Bucko Mate.

After this address of the mate’s I got a nasty taste in my mouth as if I had taken a big dose of quinine. Here was I who had never been on a square rigged ship in my life, only a schooner man, and had never been aloft. Certainly I could do my trick at the wheel, was a good steersman, but didn’t know a rope on a square rigger. But, I had the consolation of knowing that two of the crew that signed on as able seamen were Howra railway firemen and had never had a deck of a ship under their feet. (The Howra is a railroad that runs from Calcutta to Bombay).

“God,” I thought, “How will they fare with this Bucko Mate,” but soon I was destined to find out When the tug let go of us well out from the Sunderbunds at the mouth of the Hoogli we went aloft and unfurled our sails. We sped across the Bay of Bengal eight hundred miles with a freshening breeze on the port quarter. She was now blowing a stiff breeze. Seas were getting up, great big green fellows, white-capped and the vessel with all the sail she could carry was forging rapidly ahead, driven through the head seas with the force of canvas behind her, going straight in to them instead of riding over them, shipping tons of water over the forecastle head, feet of water rushing aft along the main deck. When she cleared a big mountainous sea the ship would shake herself like some huge water dog and meet the oncoming sea again. The mate was pacing the poop. I was engaged cleaning bright work close to the binnacle when who should come up on the poop but one of the Howra firemen to relieve the man at the wheel. When the fireman took the wheel from the other, wheelsman, he the relieved man, gave the course. Nor-east half by east. The fireman took the wheel but did not answer. Now when relieving a man at a wheel you must always repeat the course given by the relieved seaman, so that you have the course right. No answer was a dead giveaway showing that the fireman had never done a trick at the wheel in his life.

The Mate, nothing missing him, noticed it and, strode up to the wheel and said to the fireman “Did you sign the articles as an Able Seaman?”

“Yes sir,” he answered. By this time the ship was off her course. Instead of heading and easing her up to the big seas she had fallen off and the needle of the compass was chasing itself round the compass like a cat at play. The Mate dealt the fireman a blow that would have felled an ox and he fell an inert mass on the poop deck. I instantly jumped and grabbed the wheel and threw the vessel up meeting a mountainous sea, just in the nick of time. If that big sea had hit her when she was wallowing in the trough, it would have struck her on the beam and nothing could have saved the Mersey. She would have turned turtle and ship, all hands, and coolies also, would have been at the bottom of the Bay of Bengal.

Stooping over the now insensible fireman the mate picked him up as a cat would a mouse and threw him down the poop ladder on to the main deck and calling a couple of hands to carry the injured man to the forecastle. Walking over to me he said, “What’s your name, I’ve forgotten it.”

“Gaunt, sir,” I answered.

“Well Gaunt,” he said, “You did well. I’ll not forget it. Ease her up a little,” he continued, as a big monstrous sea was coming straight at us. I eased her and she took it beautifully, the mate and I watching it with bated breaths, and he continued to pace the poop as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

After this incident the crew in the forecastle became unsettled and muttered threats were often heard to do the mate in. One day the Mate’s watch was aloft putting new gaskets on the upper top sail yardarm. I was amongst them. We all had marlinspikes with a loop of marlin through the eye of the spike and suspended around our necks. (A marlinspike is of steel thick at one end and tapering off to a needle point, about ten inches long; with an eye in the thick end to pass the marlinspike’s twine-through, so if it fell out of our hands it would be suspended from the neck and would not fall on deck). It was about eighty five feet from the deck to the top sail yard. The Mate was standing on the deck directly underneath when suddenly a marlin spike dropped from the yardarm, and whizzing through the air buried itself about an inch and a half in the deck right at the Mate’s feet. He never moved or batted an eye.

Calling all hands from aloft he waited till we reached the deck and examined us. Tommy Payne, an A.B. had no spike and a broken marlin. “You dropped that spike,” he asked. “Yes,” said Payne, “The marlin broke.” The mate examined the two broken ends of the line. Sure enough they were frayed. “Go aloft and resume work,” said the Mate and the incident was closed. Payne had deliberately cut the marlin, frayed both ends and waiting a favourable opportunity dropped the spike aiming for the Mate’s head. The shot missed but it nearly got him. If it had hit him in the head it would have gone clean through him. It missed him by a very narrow margin.

Some time later we struck the East African coast at Cape Agulhas and ran into a terrific gale, with head winds and mountainous seas. For ten days we battled with the elements and could not pass the Cape. At daylight every morning we were on a lee shore, beat out and back again. Decks awash and forecastle flooded, nearly all the time, the two watchers on deck, and when at last we left the Cape behind the good ship Mersey had a worn out and exhausted crew. Through that gale the Mersey proved what a splendid ship she was. Like a living thing she battled with those seas. They used to pound her; they came, over the top of her with mighty blows: they used to throw her over almost on her beam ends; but she returned to the fight scarred but unbeaten although stripped of boats and deck fittings, iron stanchions broken and bent, cook’s galley gone that noble ship took her medicine and shook herself free every time, toiling and striving to free herself of the grasp of that terrific gale.

For ten days she fought wind, rain and seas and came out of it battered, bruised, but triumphant. That’s when I saw the seamanship of our Mate. Tireless, always leading in dangerous jobs, working like an able seaman, he did the work of three men and with the help of Captain Douglas, himself a splendid seaman, the ship answered every call they made, like a well-trained sheep dog obeys the call of its master. But this is not a tale of a Bucko Mate, it’s a narrative of the voyage of the good ship Mersey. At last we rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and set a course for the island of St. Helena, the last home of the Emperor Napoleon.

The weather now being good the coolies used to be brought on deck in batches and had to be watched carefully as odd ones, if they got a chance, would hop on to the bulwarks and take a header into the sea. Our grub was bad-hard tack biscuits that the maggots and weevils had left, salt pork and beef that had been killed when Adam was a boy, condemned navy stores, burnt peas for coffee, and four quarts of water per man per day. Soft bread once a week, and a plum duff on Sunday. Arriving, at St. Helena we took on sheep, fowls and geese for the consumption of the captain and officers only. Leaving, there we set a course for the South American coast.

“Everything spick and span,” was his motto and he kept us to it. About eight o’clock one morning the lookout sang out, “Land on the starboard bow,” and Cape Verde hove in sight. The weather was now unsettled; mare’s tails were scudding across the horizon; the wind coming off the land began to freshen; dark ominous-looking clouds began to gather and there was every indication of a coming storm. Coolies were sent below and hatches battered down. With the two watches on deck we were soon aloft stripping the kites off her and none too soon. The dreaded pampanero, or South American tornado, was upon us. When the pampanero struck us the ship heeled over forty five, degrees, , righted herself, shuddered from stem to stern, and then raced before that, terrible gale like a fox with a full cry pack of hounds after him. The terrific force of the wind lifted the sea and hung it at us like thrown sand off a shovel; the air was full of spume, like goose feathers; you could hardly see the length of the ship.

Then the rain started, light at first, hitting the deck like the pattering of children’s feet, increasing to a terrific downpour, it seemed the bottom had fallen out of the heavens. Leaning on the poop rail was Captain Douglas roaring out his orders to the Mate who was using all his skill and seamanship to guide the Mersey on her mad race. At times the wind would lull, stop almost, and then come back at us with redoubled force, lifting the ship almost out of the water.

The day grew dark, with a, leaden sky and with the goose feathers in the air it was almost as black as night. Towards evening the gale had spent itself leaving in its wake tremendous sea, but with a light head sail that noble ship rode her seas like a gull.

As soon as the seas abated and the weather got settled, up aloft we went and soon the Mersey had every stitch of canvas, stem sails and all, on her sticks. The Old Man drove his ship as his Mate did his crew. Up the coast we ran passing Georgetown and Demerara, leaving Barbados on our port bow. A few days later we sighted the high mountains of the Island of Trinidad. Swinging around the point at La Brae we came to anchor in the roads opposite Port of Spain, after a trip of one hundred and twenty nine days.

The boats came off to the ship and the twelve hundred and fifty coolies were soon landed and on their way to the different sugar plantations to which they were assigned. Next day (after bidding farewell to all my shipmates and officers) the Mate, gave me a hearty grip and squeezed three golden sovereigns into my palm saying, “Rum is only twopence a bottle over there in the Port and the Creole girls are good. Take care of yourself and good luck.”

I went ashore with the Captain and signed off, a free man once more with a good pay note. As I write these lines, an old age pensioner, existing on a mere pittance far away from Port of Spain, a picture like a cinema picture passes before my eyes. I see the Mersey as I saw her on a bright moonlit night lying at the break of the poop with the watch in easy call of the Mate’s whistle.

Lying on my back I gaze aloft: Lofty spars, sails all full and drawing, stemsails well out on port and starboard sides, like great wings, as with a fair wind she glides through the water like a beautiful white swan. I marvel at man’s handiwork. Today she lies in a haven of rest. She now lies in Southampton Water, England, a training ship for the White Star Line, turning out officers and cadets for steam.

Another scene passes. I see Captain John Douglas, of seventy odd summers, big moulded, a keen grey eye, leaning over the poop rail in his oilskins and sou’ wester, roaring his orders like a bull; truly a great seaman and mariner. No doubt old John has by now “crossed the bar.”

Again I see Abel Armstrong, our blue nose Nova Scotia mate who loved the good ship Mersey as an ardent lover loved his beautiful week old bride. The ship was his bride and he didn’t forget to let his crew know it. We were her chamber maids to wash her face very clean every morning and keep her dressed faultlessly. The crew hated, feared, and respected him but a deep water man is a poor hater. He soon forgets on reaching his port of discharge. Where is that Bucko Mate now? Is he still sailing the seven seas? Not on a coffee pot I’ll bet. He hated steam. Perhaps he’s on one of those Nova Scotia schooners trading to the West Indies, a master now, or perhaps owner.

Again the picture changes. I see my old shipmates of the forecastle. I fancy I hear them singing the old shanty, “Rolling Home to Merrie England,” as they beat it up the English Channel. Again I see them and the Mersey fast at the East London docks, their, long voyage finished, and the crowd in their shore going togs making for the shipping office to sign off and draw their three years pay. And then seven men from all the world, back to port again.

Rolling down the Ratcliffe Road, drunk and raising Cain,

Give the girls another drink, before, we sign away,

We that took the “Bolivar,” out across the bay. (With apologies to Rudyard Kipling).

Again I see them sitting in the Sailors Home in London as we sat in the Home in Calcutta, broke and down and out and the runner comes in and says, “Who wants to ship on an outward bound ship?” and it’s the old, old story. Up they go to the shipping office, sign on, receive their advance note, go aboard, and in no time are beating down the English Channel and as the articles call for “Three years or any port in the United Kingdom'” is the sentence! A good ship it may be or perhaps a floating hell – with a Bucko Mate.’

Browse our books here.